Dennis Hopper v. Alan Smithee: The Rival Cuts of ‘Backtrack’

A revision and distribution history of a bizarre cult thriller

In the Summer of 1988, director Dennis Hopper shot a bizarre crime thriller about a conceptual artist named Anne (Jodie Foster), who goes on the run after witnessing a mob hit. In addition to directing, Hopper also had a starring role in it as a killer named Milo, who is sent to dispatch Anne, only to fall in love with her.

The resulting movie would go on to have a fascinating, convoluted revision history closely tied to that of its various distributors, including Vestron Pictures, Carolco, Artisan Entertainment, and Lionsgate.

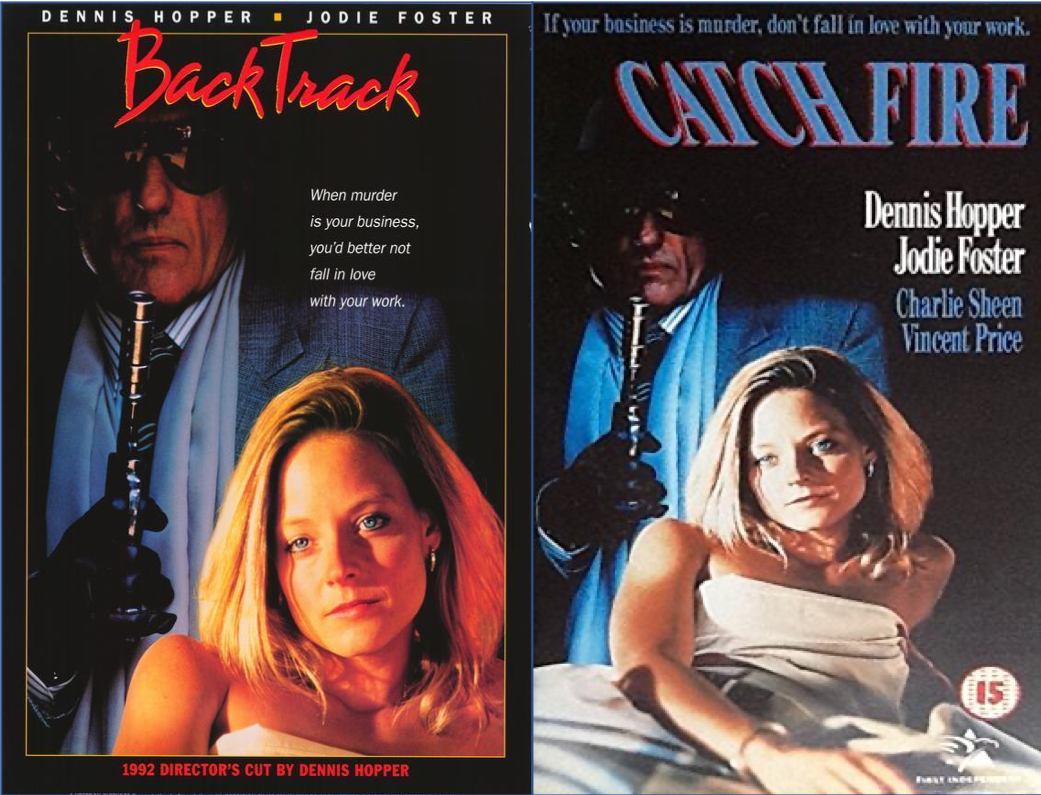

In this article, I am going to delve into the picture’s early years, explaining why it began to circulate during the 1990s in two different cuts, each with its own title and credited director. While Catchfire credited the fictional Alan Smithee, Backtrack retained the name of Dennis Hopper. In the process, I hope to discredit some popular misconceptions about the picture, as well as demonstrate how much control distributors have over what versions of a movie audiences can access.

Table of ContentsThe Vestron Bankruptcy

May 1989Dennis Hopper, now in the midst of a career resurgence, has finished work on Backtrack, which is expected to be released theatrically around September of that year.

Hopper turns in a final cut of about 2 hours - possibly with completed post-production elements, though this is not confirmed - to production and distribution company Vestron Pictures shortly before going off to begin shooting his scenes in the comedic thriller Flashback (February 1990, dir. Franco Amurri) with Kiefer Sutherland for Paramount Pictures in Colorado around May 27.

June-July 1989 (Approximately)While Hopper is away, Vestron - allegedly unhappy with the cut Hopper turned in - begins revising the movie without his participation in an effort to make it more commercial. In addition to having the picture recut and changing its score, Vestron commissions someone to reshoot the picture’s beginning and ending.*

*I’ve found, unfortunately, no accounts of Vestron’s side of the story, so much of this is based on Hopper’s own comments throughout various interviews. I assume that another filmmaker was needed for reshoots as Hopper could not participate at the time.

It is not clear precisely how much time Vestron spent on re-editing and re-scoring the film, the revised version of which ends up being 99 minutes long. What is clear, however, is that Vestron had to have stopped working around July 12, 1989.

At this point, the company had essentially gone bankrupt, forcing its executives to shut down distribution and put the company up for sale. In addition, they begin shopping Backtrack - along with multiple other completed or almost-finished titles - to other potential distributors.1 Without a distributor, Backtrack cannot be released, effectively annulling plans for its September premiere.

July-August 1989 (Approximately) Sometime either during or after the filming of Flashback, Hopper becomes aware that Vestron had recut Backtrack in his absence, even cutting the picture’s original celluloid negative. In retaliation, Hopper begins a ‘lawsuit’ against Vestron, with the intention of taking his name off the picture and, if possible, preventing the release of the revised version. Details regarding Hopper’s lawsuit, such as when exactly it was filed or what its precise demands and conditions were, are unknown.

“...and yet another movie he directed and in which he starred, “Backtrack” with Jodie Foster, may eventually be released, although not if Hopper has anything to say about it.

Hopper said he is suing the film studio (Vestron) that financed “Backtrack” to have his name removed from the credits and, he hopes, to stop its release.”

Source: Lima News, 06 Feb 1990, p. 13

However, from what I’ve gathered, Hopper’s lawsuit likely wasn’t really a “lawsuit” but rather a DGA Arbitration procedure resulting from his petition to remove his name from the picture and replace it with a pseudonym. Hopper could justify invoking the process by presenting grievances over the fact that Vestron had recut the film without him and cut negative, which could qualify as a violation of Hopper’s basic rights for consultation over editing under the DGA Basic Agreement.

Thus, when Hopper claims that he ‘sued to remove his name,’ he means that he followed the common process outlined by the DGA Basic Agreement Article 8 that allowed him to request his name be replaced with the pseudonym “Alan Smithee” in the “Film by” and “directed by” credits.* There doesn’t seem to be any way he could’ve legally banned the film from being released but he might’ve hoped that his DGA arbitration and the association of the picture with the pseudonym would have tied up the film for some time and so discouraged potential distributors from picking it up.

*Since approximately 1968-69 until 2000, “Alan or Allen Smithee” was the common DGA pseudonym used by directors who wanted to disown the films they’d worked on, with the typical reason being that the picture had been edited or re-edited against their wishes.

“He said his dissatisfaction with the result led to the lawsuit that has blocked the film's distribution.”

Source: Taos News, 21 March 1991, p. 26

February 5, 1990 As Flashback is released around February 5 1990, Hopper claims his ‘suit’ against Vestron is ongoing and that he ‘hopes’ this will block the release of Backtrack, which still does not have a distributor.

It is difficult to say with certainty, as to what effect Hopper’s arbitration/petition had on the picture’s ability to gain a theatrical release. I believe that it really didn’t have much of any effect. Rather, due to Vestron’s bankruptcy, the picture simply couldn’t be released anywhere until the rights to it had been picked up by someone else.

“Hopper is suing to have his named removed from the picture, which still does not have a distributor.”

Source: Pittsburgh Post Gazzette, 05 Feb 1990, p. 9

Catchfire in Europe

May 12, 1990 Vestron UK, the international distribution arm of Vestron Pictures, is sold to British TV company HTV.2 With this, HTV acquires the international distribution rights to the completed Vestron Cut, which had been retitled as Catchfire.*

*From what I’ve gathered, this retitling occurred some time before the sale of Vestron UK. Another title - Do It the Hard Way - reportedly appeared on a workprint of the Vestron Cut.

September 19, 1990 It is reported that the Catchfire version will receive a theatrical release in late January 1991 but only outside the US in territories such as the UK and Australia. At this point, it is known that the Catchfire version had “Alan Smithee” listed in the “directed by” and “a film by” credits in lieu of Dennis Hopper.3

From this, we can infer that some time before September 19 1990, Hopper’s petition to the DGA to replace his name with a pseudonym in the Catchfire version must’ve been approved, meaning he had won at least this part of the arbitration (assuming there were other parts that have not been disclosed).

November 1990 Catchfire is about to premiere at the London Film Festival on November 23 prior to its main release in January 1991. In time for this, Hopper provides an interview for the BBC Moving Pictures documentary series, Episode 1.08, which aired on Nov. 17.

The episode devotes a segment to the history of the Alan Smithee pseudonym and has Hopper openly discuss why Smithee is credited for Catchfire. I recommend watching his segment in full, which starts around 7:30 in.

“The Alan Smithee thing for me was… I didn’t dire– I mean, I directed that movie, what can I say? Every foot of film I directed. But I didn’t edit it. And the editing of a film is directing a film!... I turned over a 2-hour movie to Vestron that I was very happy with…

Much to my alarm, after I finished or somewhere during the shooting of Flashback, I discovered that they were re-editing the movie. Not only were they re-editing the movie, they had re-edited the movie and cut negative.”

January 1991 Under HTV, Vestron UK is officially rebranded on January 3 as a distinct film production and distribution company called First Independent Films Ltd. It has a slate of 12 theatrical features prepared for 1991, the first of which is Catchfire.4

The film is released on January 27 in UK cinemas, thus becoming the de facto European or International Theatrical Cut. Its reviews are mostly mixed, and its box office performance is less so.

June 1991First Independent releases Catchfire on VHS in the UK, retaining both its new title and the Smithee credits. Originally slated for May 22, the VHS was delayed to June 5.5 The video version is identical to the theatrical release in terms of editing, though it runs 95 minutes due to the PAL video format being slightly faster than the US NTSC format and presumably carries a 4:3 full-frame aspect ratio.*

*As the film was composited for the 1.85:1 Widescreen ratio, the video version would then have additional visual information above and below the 1.85:1 frame.

Mirroring what happened with the picture’s theatrical distribution, the VHS release of Catchfire is limited to the international market, meaning it was absent from the US. I cannot say exactly how many territories it appeared in, but in addition to the UK, it definitely circulated in Australia, though possibly via another distributor.

The Myth of the 3-Hour Cut

There is nowadays a LOT of confusion surrounding Backtrack and/or Catchfire, such as their differences, runtimes, and why the film was recut by Vestron in the first place.

Particularly strange in this regard is the unsourced-yet-often repeated narrative in both older news articles and recent blog posts, according to which Hopper initially turned in a 3-hour cut of the film to Vestron executives, who naturally chose to severely cut it down, as 3 hours was not a commercial length. This purportedly resulted in various post-production fights between Hopper and Vestron, and this is what led Hopper to remove his name from the picture.

Yet, everything I’ve found on the film’s revision history points to this narrative being a myth that originated in the UK press during the exhibition of Catchfire in British Cinemas. The earliest example I’ve located comes from a news report in The Daily Telegraph about the upcoming release of Catchfire in the UK. It states:

“The film… was originally titled Backtrack. Three hours long, it was to have been Hopper’s arty, Nineties, gangland version of his acclaimed 1969 road movie Easy Rider. Unfortunately, Hopper’s production company Vestron did not share his vision and deciding that no audience could cope with three hours of intense Hopper, cut the film to a more digestible two-hour version renamed Catchfire.”

Source: The Daily Telegraph, 19 Sept. 1990, p. 12

This is a rather dubious claim on the part of the article’s author, given that the Vestron cut was only ever around 99 minutes long and did not exist at the time of its UK theatrical release in a two-hour version. Indeed, a later review of Catchfire from The Sunday Telegraph confirms that the release was only around 90 minutes, while reiterating the 3-hour myth:

“As re-edited by the producers — almost halved from its original length of three hours — Catchfire has been reduced to a B-movie thriller… ”

Source: Sunday Telegraph, 27 Jan. 1991, p.71

To date, I haven’t found a single quote from Hopper or anyone else involved in the making of Backtrack that corroborates the claim that Hopper’s initially submitted cut to Vestron was 3 hours. On the contrary, Hopper has repeatedly maintained that the final cut he sent to Vestron before it was revised was actually 2 hours long.

The earliest quote I’ve found from the late director on the subject appears in a Feb 5, 1990 issue of the Evansville Press, about 7 months after the Vestron bankruptcy:

““Vestron (the company that financed the film) went bankrupt. They took my two-hour final cut and made a 90-minute movie out of it. They took all my music out…"”

Source: Evansville Press, 05 Feb 1990, p. 6.

A late 1990-early 1991 interview with Hopper by critic Paul Freeman* posted on Pop Culture Classics reiterates the 2-hour running time and also goes into more detail.

*The available information suggests that the interview was conducted around the time of Flashback’s release in February 1990. However, at least a portion of it must’ve been conducted in late 1990 or early 1991, as Freeman asks Hopper about the “Catchfire” version being released in Europe.

“I gave them a two-hour movie. They made it a 90-minute movie. They took a half-hour out of the hour-and-a-half movie of my stuff, threw that away, put in a half-hour that I’d taken out of the movie, of other footage, put that in, so there was now an hour’s difference..”

Source: Interview with Dennis Hopper (1990) By Paul Freeman for Pop Culture Classics http://www.popcultureclassics.com/dennis_hopper.html

Here, when asked about the European Cut of the film that was released, Hopper states that Vestron cut the movie down to 90 minutes, then removed another half-hour from that version before replacing it with an alternate 30 minutes of footage that Hopper had previously shot yet left on the cutting room floor.* In total, the movie lost about an hour of Hopper footage.

*It is not clear if Hopper means that, on top of cutting 30 minutes out of his cut, Vestron inserted 30 minutes of alternate takes, angles, shots, etc. of scenes that had already been in the original cut or 30 minutes of completely different footage. Either way, it would mean Hopper’s original final cut was significantly different from the released Catchfire Cut.

Hopper would make a similar yet somewhat different claim in March 1991.

“Hopper said Vestron, the film's distributor which owns the original negative, "cut out most of the scenes around Taos and Chimayo." The distributor also had scenes re-shot at the beginning and end of the picture and "took out about an hour's worth of footage I put in and put in an hour's worth that I took out," according to Hopper.”

Source: The Taos News, 21 March 1991, p. 26

According to this account, Vestron put in an hour of replacement footage, which would mean the movie as a whole lost over an hour of Hopper’s material, counting the Taos and Chimayo scenes, as well as the reshot sequences. Hopper may not be entirely consistent here, but his remarks indicate that, while the final cut he turned in was only 30 minutes longer than the Smithee Cut, it nonetheless had an hour or more of different material in total.*

*I have a theory that the 3-hour cut myth first began due to someone in the press recalling that Hopper mentioned the hour-plus-difference between his original cut and the Vestron Cut, and concluded that this meant Hopper’s version must’ve been over 60 minutes longer.

The Actual Running TimesNow, I think it is important to keep in mind that Hopper never actually gives in any of these accounts a precise running time for neither his original cut, nor the Vestron cut of Backtrack. The Vestron Cut would ultimately end up having a runtime of 99 minutes counting the credits, yet Hopper refers to it repeatedly as a “90-minute movie.”

In other words, he is giving an approximate running time, so we can assume he is similarly giving an approximation when he brings up his “2-hour final cut.” (My surmise is that Hopper was not counting the end credits when describing his cut as a two-hour movie and the Vestron Cut as a 90-minute movie.)

Given that he refers to the Vestron/Smithee cut as being “90 minutes long,” when its actual length is 99 minutes, we can estimate that the full length of his initial director’s cut was likely around 129 minutes. This is backed up by the fact that the 116-minute running time of the post-theatrical “director’s cut” Hopper would end up releasing on premium cable at the end of 1991 was said to have been 15 minutes shorter than Hopper’s initial cut, positioning it at 131 minutes. Splitting the difference, we can estimate that Hopper’s initial “2-hour cut” was about 130 minutes long in total.

All in all, the available evidence suggests that the fabled 3-hour cut never existed.

Backtrack to US Cable

August 1990 - July 1991On August 10 1990, still-bankrupt Vestron Pictures enters into negotiations to sell all its remaining assets to LIVE Entertainment, which was essentially a home entertainment subsidiary of the independent film production company Carolco Pictures.6 The acquisition by LIVE would not conclude until almost a year later, on July 22, 1991.7 With that, Carolco/LIVE came to own the domestic US distribution rights to the Vestron Cut, but it also should’ve gained access to all the materials pertaining to it, including the original film negative.

August-October 1991 On Oct 31, 1991 news breaks that Hopper is working on a director’s cut of Backtrack, which would include the film’s original title and feature Hopper’s name in the ‘directed by’ and ‘a film by’ credits, for a premiere on premium cable television channel Showtime, with an approximate December 12 release.

This means Hopper must’ve finalized a deal with Carolco and Showtime sometime earlier, likely in August or September 1991.

““According to Kat Stein at Showtime, "Dennis is re-editing it right now and it will be shown on Dec. 14 at 8 p.m. (probably eastern time)."”

Source: The Taos News, 31 Oct 1991, p. 26

Hopper, however, did not merely re-create his initial cut. He had re-assessed the film’s assemblage and chose to cut Backtrack down by about 15 minutes.8 The final running time of the director’s cut would be approximately 116 minutes.*

*Among other things, Hopper reinstated a notable amount of deleted scenes set in Taos, New Mexico that showed the art and culture of the area, something that was very important to him. I don’t wish to go into detail here about specific editorial differences between the two cuts but anyone interested should read this report on Movie-Censorship.

Mid-December 1991 The Backtrack director’s cut ultimately premieres on Saturday, December 14 on Showtime.9 I can’t say just how well it was received overall but the movie - previously unseen in the US - definitely generated some positive press here and there.

Robert Strauss claimed the film is ‘not another mob movie’ that is ‘well worth your time.’10 Meanwhile, Dick Behnke claimed to “love” the movie, which he described it as a “bizarre” art film that was “destined to become a cult classic…”’11

The new cut in any case must’ve been a source of validation to Dennis Hopper, who managed to restore his personal artistic vision and likely believed the film’s primary intended audience would never see the Vestron cut.

Showtime or Carolco?

Accounts vary, as to who exactly commissioned the production of the Backtrack director’s cut. Per Scott Eyman, the main party responsible was Carolco Pictures:

“After Hopper delivered ' “Backtrack” to the studio he went off to make a movie with Kiefer Sutherland. Vestron then turned the picture inside out, re-shooting the beginning and the end, re-cutting the negative…

Enter the white knight. Carolco, the company that bankrolled Terminator 2,” bought Vestron’s assets and gave Hopper the money to go back and re-cut the negative.”

Source: The News Tribune - 13 Dec 1991, p.70

By contrast, Bob Wisehart’s article on how and why Showtime would pick up theatrically unreleased movies gives credit to the premium network, citing its Vice President Matthew Duda:

“Whatever the title, it got a limited run in Europe before Showtime bought cable rights to this previously unseen (in the United States) film. At that point, explained Duda, “We went back to Dennis (Hopper) and said 'Restore it the way it should be,'" which Hopper was happy to do.”

Source: The Sacramento Bee, 19 Apr 1992, p. 162

So, did Carolco/Live executives make the decision to convince Hopper to recut the film and get Showtime to release it? Or did Showtime bring up the idea to Hopper and got Carolco on board? Both possibilities seem valid.

Either way, it is safe to assume Carolco, which ultimately owned the distribution rights, must’ve had some interest in revisiting the movie, given that it could’ve simply released Vestron’s Cut in the US. Perhaps, the executives in charge looked at the not-great reception of Catchfire overseas and decided that releasing a version on US television with Hopper credited as director would ultimately be more profitable than releasing any version of it in theaters.

It is important to understand that Cable and VHS were both theatrical aftermarkets that provided movies with a second chance to find an audience. By the mid-80s, it was not uncommon to find alternate cuts of films coming out on both platforms.

And towards the end of the decade, direct-to-cable and direct-to-video premieres for previously unreleased theatrical features was becoming a popular new strategy. For a distributor, this had the benefit of avoiding marketing, exhibition, and other theater-related costs, allowing a not-so-commercial work to provide higher return on investment. For a premium channel like Showtime, this was an opportunity to acquire exclusive films with theatrical production values at a reduced cost.12

Showtime already had a reputation at this point of providing Hollywood directors the opportunity to reissue their films in a new cut that better reflected their vision.* It also helped that it had a close working relationship with Carolco, having signed a distribution agreement in 1988 that gave the Channel “exclusive pay cable rights in the United States for all of the studio's releases through 1992...”13

*In December 1987, for instance, Michael Mann had released a director’s cut of Manhunter (1986) on The Movie Channel.

It is possible that Backtrack fell under this deal. Even if it didn’t, Carolco and Show-time’s history of collaboration, combined with the rising potential of the cable and video markets, likely made the Backtrack director’s cut project a viable investment.

The Director’s Cut VHS

March 1992

LIVE Home Video, a subsidiary of LIVE Entertainment, releases the Backtrack director’s cut on videotape in the United States on March 11, 1992.14 For almost a decade after this, the director’s cut - with Hopper’s name in the “directed by” and “film by” credits - would effectively remain the sole version available to American audiences and so the only point of association with the Backtrack title.*

*It is worth reiterating that the film was composited for 1.85:1 widescreen and so presumably protected for television release. The VHS version contains a full-frame 4:3 transfer, meaning it now has additional visual information above and below the 1.85:1 area of action. The Showtime cable release likely had this as well though I can’t definitively confirm this.

This effectively formalized the distinction between Backtrack (the director’s cut) and Catchfire (not the director’s cut) throughout the 90s. In effect, it positioned Backtrack as the legitimate and authentic version of the movie, suggesting to anyone aware of film variation that any other cut was a lesser, qualitatively inferior variant. As the latter circulated with a different title, a different assemblage, and with Smithee’s name in the credits, the two versions were now relatively easy to distinguish.

Unfortunately, this would not last long.

Despite being widely available in the US on VHS in the 90s, the director’s cut would vanish from domestic circulation in the 2000s, while Catchfire - now mysteriously titled Backtrack again and with Hopper’s credits restored - would become the sole cut released in the US on DVD courtesy of Artisan Entertainment, making it the dominant variation of the film available from that point forth.

But that is another story, one that you can read here.

Anne Thompson, “Risky Business,“ LA Weekly, 10 Aug 1989, 31.

The Journal (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Tyne and Wear, England), 12 May 1990, 13.

The Daily Telegraph (London), 19 Sept 1990, 12.

Variety, 20 Jan 1991, https://variety.com/1991/more/news/ambitious-plans-on-tap-at-new-htv-subsid-99127362/.

The Sutton Coldfield News, 10 May 1991, 14.

The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Aug 10 1990, 24.

Los Angeles Times, 22 July 1991, 143.

Eyman, The News Tribune, 13 Dec 1991, 70.

Asbury Park Press, 13 December 1991, 44.

Ibid.

The Taos News, 12 December 1991, p.24.

Bob Wisehart, “The mysterious case of ‘Boris and Natasha.’ The Sacramento Bee, 19 Apr 1992, p. 160-162. ”Joe Baltake, “Direct-to-Video: A new way of releasing movies.” The Sacramento Bee, 19 Apr 1992, p. 161-162.

New York Times, May 20, 1988, Section D, Page 14

The Miami Herald, 06 March 1992, p. 214.