Did the DGA revoke 'Catchfire' director's pseudonym?

Dennis Hopper's Credit Mystery, Plus: Linton, Cronenberg and Araki.

It’s official: following a long absence from post-VHS home video formats in the US, the 116-minute director’s cut of Dennis Hopper’s Backtrack (1991) is finally arriving on Blu-Ray via Kino Lorber on April 25, 2023. In addition, the disc will include the film’s 99-minute ‘theatrical cut.’ The labeling, however, is deceptive, as the so-called ‘theatrical cut‘ is not the 1991 Alan Smithee version that was released under the title Catchfire in British and Australian cinemas.

Instead, Kino Lorber admitted that it is putting out a nearly identical, yet slightly revised version that has been circulating in the US on home video since 2001. Despite having the same editing as the Smithee Cut, which Hopper disowned, it actually retains the original title Backtrack and restores Hopper’s name to the “directed by” and “a film by” credits, in lieu of the pseudonym Alan Smithee.

Thus, it’s the version Dennis Hopper disowned, but with all onscreen traces of his having disowned it missing!

Why was this version released? And how is it possible that it came to exist in the first place? I can only provide a theory, which is that this is ultimately the result of Hopper badmouthing the Smithee Cut in the press, which led the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) to revoke his pseudonym.

To illustrate this, I will delve into the distribution history of this revised version, which I will refer to henceforth as the “Backfire Cut” to distinguish it from both the director’s cut and the Smithee-credited international theatrical cut, and discuss what it implies for filmmakers’ ability to use pseudonyms on alternate cuts.

Finally, in a short post-script following the Backtrack essay, I will highlight a few recent director’s cut-related stories that I find interesting.

Contents:P.S. Director’s Cut News and Views

The Itunes Snafu

I want to begin by first explaining how I realized that the only version of Backtrack currently available on DVD/Blu-Ray and Streaming in the US was neither the Hopper cut, nor the Smithee cut, but actually a third version that nobody really talked about as a unique variant.

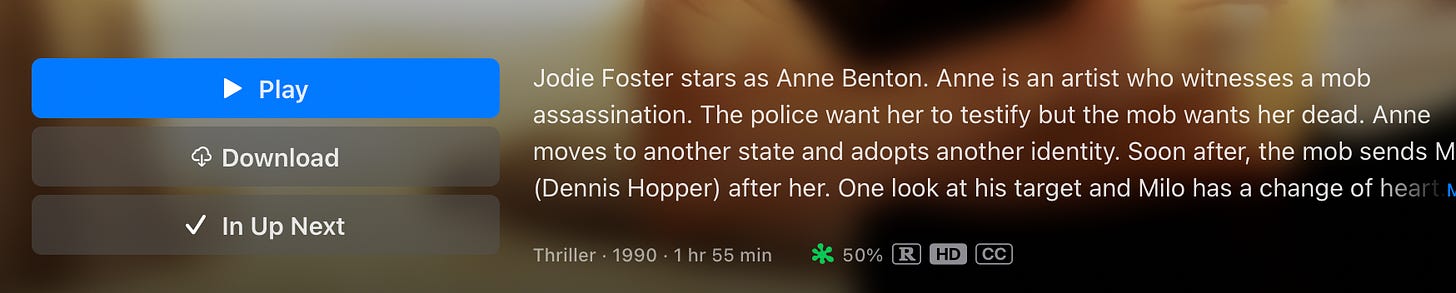

Back in 2021, I became interested in seeing Backtrack and Catchfire back-to-back after discovering that the latter version was available for free streaming on Amazon Prime. Even though the Amazon version didn’t have the Smithee credit and the Catchfire title, it had the right duration, so I didn’t make anything of it. I then started searching for a streaming copy of Backtrack and it popped up on Itunes/Apple TV. Apple’s preview menu listed the film under the title of Backtrack, credited Dennis Hopper as the director, and advertised its runtime as 115 minutes.

And it looked pretty cheap – just 7 dollars – so I decided to purchase it, as no other digital streaming platform appeared to have the director’s cut.

When I hit play, however, I was taken aback, for I realized that, rather than getting the director’s cut, I had instead received the exact same 99-minute cut that was available on Amazon. Indeed, when I checked the entry for the film inside my Apple TV movie library page, its poster title became Catchfire, even as the database entry continued to list it as Backtrack. Naturally, I had some questions, such as : “Why was the same cut showing up under both titles? Were the folks at Apple TV not aware of which cut of the film they actually had? Was the distinction deliberately obfuscated to trick cinephiles interested in the director’s cut into buying the disowned version?”

Clearly, something weird was going on here. I got curious and started digging.