The origin and evolution of the "Director's Cut"

From a creative right to cable and video revision

The term “director’s cut” is generally thought to designate the definitive version of a theatrical feature film as intended by its director. Consequently, its release is believed to be motivated by wholly artistic interests. In reality, the term can refer to different versions of the same picture in different contexts.

And more often that not, a director’s cut technically constitutes a retroactive authorial revision made possible by an intersection between the creative interests of Hollywood filmmakers and the commercial interests of film distributors.

This article will illustrate these points by examining the history of the “director’s cut” as a concept, outlining its origin in the 1960s and its redefinition by the new home viewing technologies of the 1980s. In the process, it hopes to clear up some common misconceptions about this type of alternate cut and its role in the film industry.

ContentsCreative Rights: The Origin of the “Director’s Cut”

In its original formulation, the term “director’s cut” specifically referred to an unfinished pre-theatrical version of a film assembled by the director (usually with the editor) without interference at the start of the post-production process. The creation of this version is, in fact, standard procedure in the American film industry today. This is attributable to the efforts of the Director’s Guild of America (DGA) to contractually guarantee a number of basic editorial rights to its members.

In 1964, a DGA subcommittee led by Elliot Silverstein proposed a bill of “creative rights” for film and television directors during negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).1 At the time, many DGA members reportedly felt “that the producer interferes too much” and desired “more autonomy during actual production and editing.”2

The April 1964 proposal meant to change the status of the director to that of “someone who should take part in all aspects of the motion picture process.”

In essence, Silverstein and his colleagues sought to redefine the director as an artist, legitimating him as the individual creative authority responsible for the film in its totality. Central to this was the establishment of the “director’s cut,” a contractual right to edit the film without any outside interference for as long as necessary to assemble a finished cut.

As Silverstein describes it, the director's cut was supposed to represent the purest expression of the director’s personal vision. Free from any outside influence, it “was to be definitive” and what the director ideally “wanted to appear on the screen."3 In effect, the proposed “director’s cut” was the equivalent of “final cut”– the right to determine the cut of the film that viewers ultimately see in theaters.*

* Note that “final cut” can refer to both the right to make such a version and the version itself. The word “final” underlines how the cinema was perceived as the only space of film exhibition.

Unsurprisingly, final cut has historically been long desired by Hollywood directors. According to Tino Balio, a director’s right to final cut existed in the days of silent cinema, but came to an end by the 1930s, when producers assumed primary control over editing following the standardization of film production.4 This is in line with Sarris’ finding that final cut was a rare privilege in the 30s and 40s during the studio system and that it did not translate from one project to another.5

Had the AMPTP accepted the DGA’s terms as proposed, any Hollywood director with a standard DGA-based contract would have the right to final cut by default. Naturally, the producers rejected the proposed redefinition of the director on the grounds that it was “all-encompassing” and neglected the roles of other participants in the filmma-king process, such as the producer and editor. But eventually they agreed to make the right to a director’s cut a standard part of contracts in autumn of 1964.6 However, rather than guaranteeing directors absolute authority, the new contractual right was a compromise that left the last word over a theatrical release’s editing to the studio.

Article 7 in the 2017 DGA Basic Agreement, which focuses on the creative rights of the director, makes clear that a “director’s cut” is only the first cut the director presents to the studio before it undergoes revisions with input from other individuals, such as producers, studio executives, and preview audiences. It is also notably far from “complete” in the sense that other aspects of post-production, such as sound mixing and visual effects, are missing or subject to change. And while the director has legal right to make this cut without interference, he must do so within a pre-determined amount of time, such as within ten weeks after the end of principle photography.7

So, while virtually every Hollywood filmmaker since 1964 has had the basic right to assemble a director’s cut when working on a movie, he or she is not guaranteed absolute control over what audiences ended up seeing in theaters. Unless the director manages to negotiate the right to “final cut” as part of his contract, the theatrical cut is bound to have significant editorial differences from the director’s cut.*

*And even in those instances when the filmmaker has secured final cut, full equivalence of assemblage between the theatrical release and the pre-theatrical director’s cut is not guaranteed. It is only natural for directors to change their minds in the course of editing, resulting in changes that can range from minute alterations to specific lines of dialogue to the full excision of major sequences.

Basically, what this means is that for practically every Hollywood film that has come out in theaters since 1964 there exists at least one alternate pre-theatrical director’s cut. Audiences are often unaware of these work-in-progress versions, as they are not made accessible to the public. Nonetheless, they exist and play crucial role in a film’s journey to the screen, while attesting to the fact that editing is a fluid process.

Cable and Video: The Post-Theatrical “Director’s Cut”

A series of developments occurred throughout the 1980s that resulted in film audiences becoming more familiar with the idea that movies could exist in multiple versions. In the process, the “director’s cut” gradually acquired a new definition within cultural discourses as a complete version of a film that the director always wanted to release in theaters and the representation of his singular artistic vision.

As mentioned previously, the DGA managed to secure the right of director’s cut in 1964. From this moment forward, any DGA member working in Hollywood was now contractually guaranteed at least a measure of editorial influence over a picture and final credit in the main titles.8 And while studios did not standardize final cut, they did become generally more amenable to providing directors with creative freedom, especially when it came to editing, from the mid-1960s to the late 70s.

However, everything changed following the dissolution of United Artists (UA) in 1981 after the critical and commercial failure of Heaven’s Gate. Directed by Michael Cimino, the Western epic reportedly cost about 44 million dollars and was exhibited in two different theatrical cuts, both of which failed at the box office.9

Crucial to the lack of success was the film’s association in the media with budgetary excess and directorial indulgence, of which the 219–minute running time of the film’s theatrical cut was emblematic. Following highly negative critical reactions to the initial press screening in 1980, Cimino and UA pulled the film out of theaters and re-edited it for a re-release down to about two-and-a-half hours.10 Though reviews of the shorter 1981 cut were slightly more positive than those of the 1980 cut, this ultimately did not help the film find financial success. Heaven’s Gate thus turned into a cautionary tale of what happens when a director has too much freedom, leading studios to become far less willing to grant control over a picture’s assemblage to directors.

As a result, multiple 80s films would subsequently become famous due to behind-the-scenes conflicts between studios and directors over the assemblage of the theatrical release.11 However, these events coincided with the emergence of ancillary markets tied to the new home viewing technologies of pay-cable and video.

Embittered auteurs came to view these delivery platforms, which were not bound by the duration and content restrictions of theaters, as opportunities to reassert their authorship over film texts. Meanwhile, distributors recognized that they could become a substantial source of supplemental revenue following a picture’s theatrical run. These interests came together to foster the rise of alternate cuts.

Though there were several different categories of such versions, arguably the most prominent was – and continues to be to this day – what I define as “authorial revisions” or “revisionist authorial cuts.”

While typically assembled by a director following a picture’s theatrical release for exhibition on premium cable, VHS, or laserdisc, these cuts claim to represent the “original” version of a film text, thereby promoting the director as the film’s author and positioning themselves as works of art. In this context, “director’s cut” was one of several labels used to designate and market such revisions.

Even though authorial revisions began appearing as early as 1980, however, “director’s cut” does not appear to have come into use until approximately January 1988, when Manhunter (dir. Michael Mann) premiered on premium cable’s Showtime-The Movie Channel (S-TMC). Here, it appeared as the first entry in a new “occasional Movie Channel feature” called “Director’s Cut.”12

As the title indicates, it was intended to provide filmmakers with “the opportunity to re-edit their theatrical releases so that they closely resemble the director's original vision.”13 Evidently, Manhunter did not garner high ratings, for the “Director’s Cut” feature never again appeared on S-TMC. Nonetheless, “director’s cut” began to be increasingly used to refer to such authorial revisions from that point forward.

The following chart, which arranges a number of titles in the order of their revisionist cuts’ release dates, should illustrate what I mean.

Popular Myths about the Director’s Cut

The most common justification offered by filmmakers for the production and distribution of a post-theatrical director’s cut is what David Andrews defines as “the bad old story,” which refers to any narrative that presumes an opposition between the commercial interests of distributors and those of “cinematic artists, especially auteurs.”14

It goes something like this: an auteur loses or is denied control over a big budget Hollywood studio picture in post-production, with the distributors ultimately releasing a butchered or compromised version in theaters. Initially unable to realize his vision, the auteur continues to fight for it, eventually gaining the opportunity to present it to audiences in a post-theatrical context several years after-the-fact.

The circulation of a director’s cut preceded by such a narrative is typically held up within cultural discourses as an instance of art triumphing over commerce and an individual creative vision overcoming the inherent restrictions of industrial studio production. Playing into this, directors tend to position themselves as artists/authors by claiming to reverse changes or compromises made for commercial distribution in the new cut, thereby realizing the film’s true artistic potential. In turn, this legitimizes ancillary markets used to be exhibit the new cut as the sites of creative freedom, authorship, and originality, in contrast to the theatrical cinema.

Over the course of 30+ years, the proliferation of post-theatrical director’s cuts alongside such narratives has given rise to two popular myths:

The director’s cut is always the result of a filmmaker being denied final cut over a theatrical release.

The director’s cut is the definitive version of a film.

Let’s consider the first myth. Putting aside the fact that it doesn’t take into account the existence of the pre-theatrical director’s cut, it fails to consider that there can be other potential reasons for creating a post-theatrical director’s cut.

For instance, a director may actually collaborate with the distributor and willingly work to release an audience-friendly, studio-approved version of a picture in theaters with the foreknowledge of (or in exchange for) getting his own preferred cut distributed on video later. In this case, the director’s cut is the result of collaboration between the distributor and the auteur, rather than a struggle for control. Multiple titles from the filmographies of Zack Snyder, Ridley Scott, and James Cameron may qualify as examples of this.

Similarly, a director can simply change his mind over time and reconsider some of the earlier choices he had made in the editing of a picture. This tends to be often the case with director Michael Mann. As previously mentioned, Manhunter could very well be the first film to receive a post-theatrical director’s cut. But by Mann’s own admission, the reason he decided to make a new version for cable is that he saw an opportunity to “go back to the editing room and take advantage of hindsight.”15 Clearly, his vision for Manhunter continuously evolved, for Mann would recut and reissue the film in further “director’s cut” variations approximately 3-4 more times.

This brings us to the second myth, which posits that the director’s cut is the definitive version of a movie. In this case, “definitive” appears to mean both the “best” and the “last” possible version. As the Manhunter example shows, this really isn’t the case.

In fact, it is not uncommon for certain auteurs, such as Mann, Lucas, and Coppola, to make successive authorial revisions of a picture, each of which purportedly constitutes an improvement over its predecessor and the ‘true’ final edition. New technologies in particular often provide incentive to revise older works.

What this shows is that there is really no limit when it comes to authorial revision in general and the post-theatrical director’s cut in particular. That is, the same picture can give rise to a potentially infinite number of director’s cuts, and not a single one of them will be truly authoritative. In the end, as long as art and commerce continue to find common ground, more such versions will come into existence.

This is not meant to condemn the creation of director’s cuts, pre-theatrical or post-theatrical, but rather to suggest that they are a fundamental part of Hollywood filmmaking, the rule rather than the exception. Accepting this is crucial to recognizing that all films are inherently unstable texts that change over time.

If you like this article, then please, by all means, share or cross-post it! Have any thoughts on the post? Then be sure to leave a comment!

Want to learn more about alternate cuts, versions, editions, etc., or just read some interesting film and TV criticism? Then sign up for my newsletter!

Lyndon Stambler, “Director’s Cut,” Director’s Guild of America, Spring 2011, http://www.dga.org/CreativeRightsBill.

Variety, 26 Feb 1964, 5.

Ibid.

Tino Balio, Grand Design: Hollywood As a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930-1939 (New York: Scribner, 1993), 77-79.

Andrew Sarris, “Towards a Theory of Film History,” in Movies and Methods, ed. Bill Nichols (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 1: 246.

Robert Markowitz, “Visual History with Elliott Silverstein,” Director’s Guild of America, May 17, 2002. https://www.dga.org/Craft/VisualHistory/Interviews/Elliot-Silverstein.aspx?Filter=Full%20Interview

“Article 7, Section 7-500: Editing and Post-Production,” Director’s Guild of America Basic Agreement of 2017, 72-88.

Steve Pond, “A Guild is Born,” DGA Quarterly 2, no.4 (Winter 2006), https://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/0604-Winter2006-07/Features-A-Guild-is-Born.aspx.

Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry (Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 340.

Steven Bach, Final Cut: Dreams and Disaster in the Making of Heaven’s Gate (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985), 348-376.

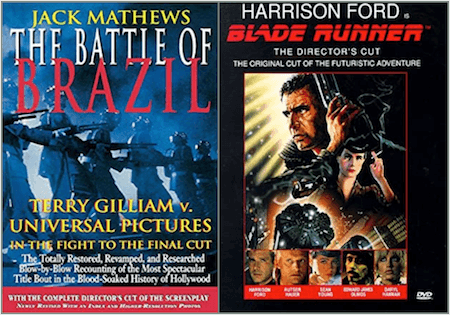

See Paul M. Sammon, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner (New York, NY: HarperPrism, 1999). Also, Jack Mathews, Terry Gilliam, Tom Stoppard, and Charles McKeown, The Battle of Brazil (New York: Applause Books, 1998).

"`Manhunter' on TMC." Los Angeles Times, 31 Dec. 1987.

Jim Emerson, "Trailers," Orange County Register, 10 Jan. 1988.

David Andrews, Theorizing Art Cinemas: Foreign, Cult, Avant Guard, and Beyond (Austin: University Of Texas Press, 2013), 191.

John J. O'Connor, "TV VIEW; TV's Film Editors Giveth as Well as Taketh," New York Times, 12 Jun 1988, Late Edition (East Coast).