On the Unseen Alternate Endings of "Unbreakable" and "Glass"

M. Night Shyamalan's superhero trilogy could've gone in different directions

Movie endings can change before, during, or after shooting as a film makes its way to theatrical release. Sometimes, filmmakers recognize that the original ending simply doesn’t work. Other times, audience feedback leads the studio to demand changes. In any case, an ending to a film is not set in stone until the picture is released.

It is not uncommon for removed alternate endings to subsequently appear on DVD, Bluray, etc., bolstering the secondary market value of the picture. But in some cases, media producers for one reason or another might choose to conceal from audiences the fact that the film could’ve ended differently.

Perfectly illustrating this is M. Night Shyamalan’s superhero trilogy (aka the “Eastrail 77 trilogy”). All of its installments - Unbreakable (2000), Split (2016), and Glass (2019) - have had their endings altered to some extent prior to theatrical release.

However, only the alternate ending of Split has ever received circulation, appearing on the picture’s homevid releases as a bonus feature. Meanwhile, those of the first and third film, respectively, have remained inaccessible to the public, as well as virtually unmentioned in behind-the-scenes interviews, as though they do not exist.

In this article, I want to to show that these endings indeed exist, provide some potential explanations about why they had been revised or scrapped, as well as discuss how their removal had impacted the overarching narrative of the Eastrail 77 trilogy.

Table of Contents

1. Unbreakable Alternate Ending: David Walks Away

2. Glass Alternate Ending: Staple is a government agent Unbreakable Alternate Ending: David Walks Away

To my knowledge, the alternate ending to Unbreakable at the moment can only be inferred from various bits and pieces of evidence that suggest the picture’s ending underwent a slight yet crucial change very late into post-production.

To recap, much of the story focuses on the relationship between David Dunn (Bruce Willis) and Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), with Elijah gradually leading David to accept the fact that he is a virtually invulnerable real-life superhero after he becomes the only survivor of a massive train derailment. The picture initially appears to present Elijah as a largely benign mentor figure to David.

The ending, however, establishes that Elijah is actually the film’s villain, revealing that he had orchestrated the derailment of David’s train, not to mention multiple other incidents, all for the purpose of proving that superheroes can exist in real life and so establishing that he himself wasn’t born as a broken man for no reason.

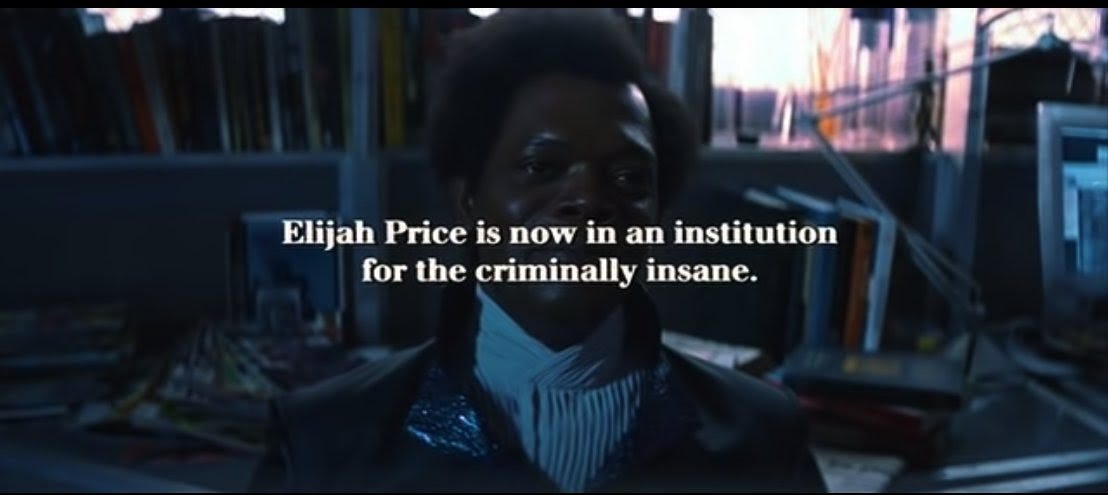

What is interesting is that the fates of the two main characters are communicated to audiences in the final scene via superimposed texts, in a manner calling to mind a biopic. Both refer to events that take place after the big Elijah reveal. The first establishes that David gave up Elijah to the police, while the second informs us that Elijah has been placed into a mental institution.

Evidently, the scene wasn’t really designed or filmed with those text inserts in mind. For one thing, they disrupt the scene, appearing over freeze frames as the final David/Elijah scene is still playing. There aren’t really any shots or frames specifically meant for them, no new footage or imagery that actually depicts the events being described in them. The inserts could’ve very easily appeared against a black screen after the scene ended. And had they been cut, you’d never really know they were there.

Now, imagine if the scene played out without stopping, without the freeze frames and inserts. In this case, the film would end with David simply walking away devastated after Elijah reveals his true nature. The viewers would not be privy, as to what happened next. (At least, until a potential sequel would resolve these events.) They would not know what David did next or if Elijah ever faced any consequences for his crimes. The last thing we would see is Elijah smiling, having achieved his goal and recognized that he indeed has a purpose in the world.

Without those text inserts, the film would have very little sense of narrative closure. Its open-ended final scene could very well be interpreted as a cliffhanger meant to entice audiences to return for a sequel. Indeed, I’ve come to believe that the final scene was initially meant to function as such. That is, the texts were added late into post-production in order to add more closure to the picture and remove the ambiguity.

For one thing, there is a script draft of Unbreakable dated October 8, 1999 available online. (While interviews confirm that this is not the final draft or shooting script of the film, it is quite close.) The scripted ending has some very interesting differences from what we see in the theatrical release. Elijah and David have much less dialogue after David recognizes the truth and there is no beat, where Elijah embraces the idea that he is and always has been Mr. Glass.

But more importantly, there are NO TEXT INSERTS mentioned here whatsoever.

In fact, the final shot as written depicts David leaving and seemingly blending in with the “ordinary people, walking on an ordinary street, in an ordinary city.” There is no indication in this draft that David’s next step is to have Elijah arrested and/or institutionalized. Indeed, the description suggests that his shock at Elijah’s reveal has led him to reject Elijah’s claims and perhaps attempt to return to a non-superhero life, to live as a normal or ‘mundane’ person.

What we have here is a much more ambiguous and open-ended conclusion than the one in the released film, indicating that Shyamalan had at one point the intention of not giving viewers any true resolution, but leaving it more of a cliffhanger.

An interview with M. Night Shyamalan for Creative Screenwriting confirms that the original ending was that David simply left and blended in with the crowd and that Night did not want full closure on David’s story. The writer-director does not clarify, as to whether or not the final shooting script or ‘revised draft’ of Unbreakable would’ve had the text inserts that appear in the theatrical release.

But his interview does corroborate the fact that the plot point about David giving up Elijah was not always planned to occur at the end of the picture. (The conversation largely focuses on the twist/reveal of Elijah’s true nature, which the final film places far more emphasis on than the Oct. 99 draft. )

Your original ending of Unbreakable had David slipping into a crowd of “ordinary people, walking on an ordinary street, in an ordinary city.” You changed the focus of the ending slightly in the revised draft of the script. Why?

I think the greatest twists are when things change fundamentally. The two films I always use are Planet of the Apes and Psycho, where what you thought you saw you did not see. In Unbreakable what you thought you saw was a superhero becoming a superhero. But that’s not what you saw. The whole movie twists and turns on its head. It’s a kind of fundamental change that I was going for, that I didn’t quite get before.

There’s also an entry on the picture’s IMDB page under “Alternate Versions”, which states that early previews of the film

“didn’t have the superimposed text ending, leaving a more open ending. This version was released in France in theaters, but the text was next included in TV, video and DVD.”

I have not been able to confirm, whether or not this claim is true.

EDIT: A reader has corroborated that when he saw the film theatrically in France, indeed there were no text inserts in the ending sequence. He was surprised to see them appear when he later got the film on DVD. See comments section below.

I don’t know how or why the original ending came to appear in the French theatrical version of Unbreakable. But it is likely that the ending was changed in response to early test screenings. Preview audiences may have wanted more resolution, compelling M. Night Shyamalan to add those texts to satisfy them.

Studio input could’ve also played a role in this. When discussing the film for the EW Oral History in 2015, Nina Jacobson, who was the president of production at Disney at the time Unbreakable was made, curiously stated:

I remember conversations about the ending. The hero walking away from the villain always troubled me. And to leave so much unknown was something I wondered aloud about to Night. So maybe there should be a sequel.

What Jacobson describes here seems far closer to the scripted ending of the Oct. 99 draft than the actual ending of the movie. More than that, her statement plays into the idea that the story of Unbreakable was meant to continue in further films. Assuming Shyamalan had a desire to create a film trilogy at the time, an open ending for Unbreakable makes a lot of sense.

The logical conclusion is that an alternate ending for Unbreakable, where the final scene plays without the superimposed texts, indeed exists. (Or at least existed at one point in the film’s making.) Its differences from the theatrical ending in terms of editing are minor. Yet they carry considerable narrative impact, indicating that Elijah’s institutionalization was very much a last-minute plot development added to the picture during post-production after test screenings and/or studio input, rather than one that had been pre-planned. Its presence essentially meant that any follow-up would have to deal with his having been arrested and committed.

Had the text-less ending been the one to appear in theaters, the story we would ultimately come to see in the sequels may have turned out to be quite different, for there is no guarantee that Elijah would’ve ever been made to pay for his crimes. For instance, one can imagine an alternate story, wherein David never gave up Elijah and instead simply chose to go into hiding and abandon his call as a hero.

This means that the plot of Glass, the majority of which takes place within the setting of the mental institution where Elijah had been incarcerated, can be seen as a natural byproduct of the late decision to add the texts to the ending of Unbreakable.

Glass Alternate Ending: Staple is a government agent

The ending of Glass (2019) tends to be presented within the media as the “ending that always was,” as though M. Night Shyamalan had been planning for the overarching story of his superhero trilogy to conclude the way it does since the release of Unbreakable almost 20 years earlier. As the case with the ending of Unbreakable indicates, the reality is much more complicated than that.

The plot of Glass had evolved in the course of the script’s development, filming, and post-production. Most notably, the ending was changed at some point, possibly after the initial ending had already been shot.

The big difference between the originally intended ending and the theatrical ending revolves around the character of Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson), whom the film initially introduces as a psychiatrist seeking to convince the film’s three superhuman characters - David, Elijah, and Kevin (James McAvoy, introduced in Split) - that they are simply normal people with delusions of grandeur.

In the released theatrical version, the ending reveals that Staple is not a psychiatrist at all, but rather a member of an ancient secret society dedicated to suppressing the existence and public awareness of superhuman beings. In the earlier pre-theatrical version, Staple apparently had the same purpose and motive. But rather than a member of a secret society, she revealed herself to be an agent of the U.S. government. In other words, there was no secret society. In its place was a clandestine agency dedicated to preventing the rise of superheroes.

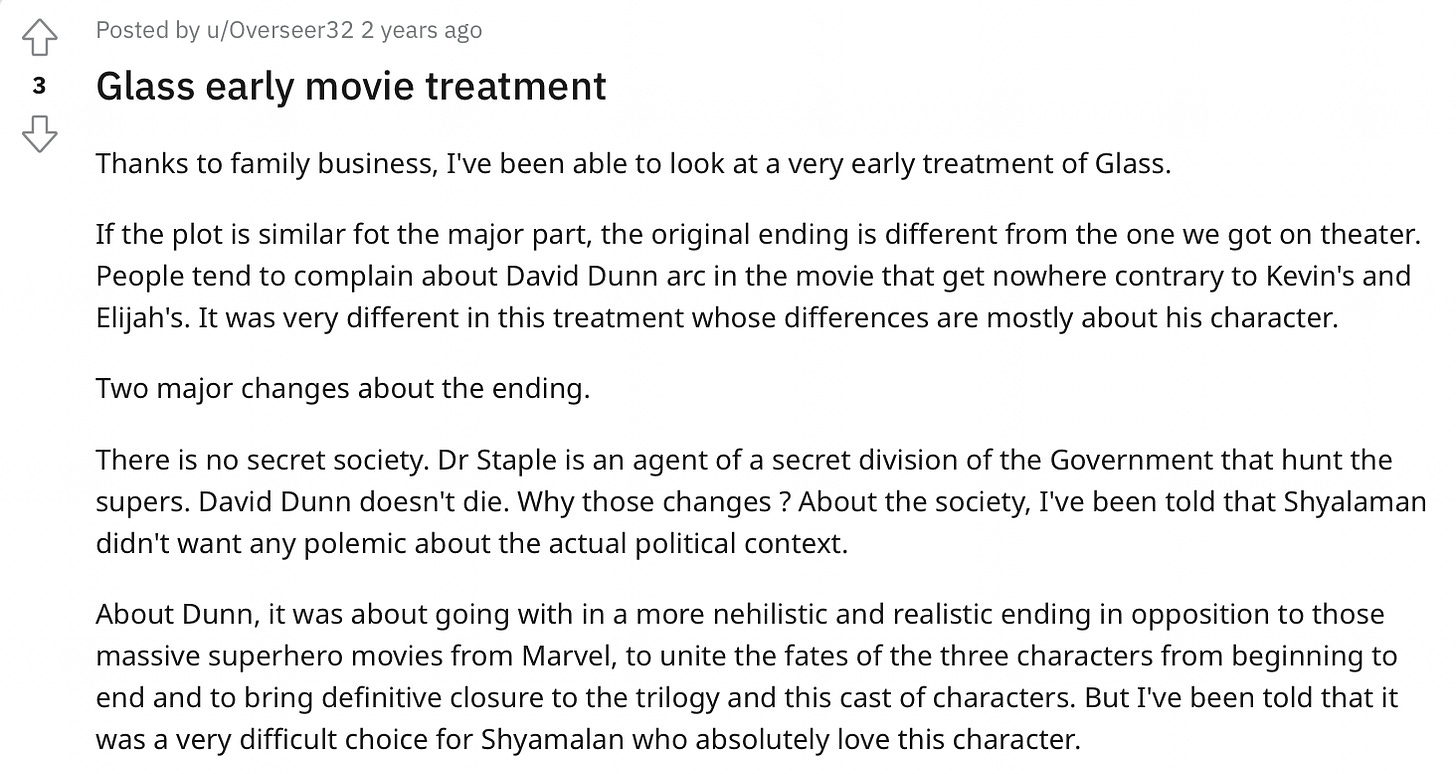

Evidence that the “government agency” version of the ending was developed can be found across various sources. One such source is a July 28, 2019 reddit post that compares an early treatment (basically an outline or summary of a movie that is created prior to the writing of a complete screenplay) of Glass to the theatrical release.

According to its author Overseer32, while the overall plot of the film was very similar, there were two notable changes to the ending. Here is an excerpt from the post:

The first major difference suggests a similar yet distinct conception of Ellie Staple’s character. Meanwhile, the second indicates a radically different resolution to the character of David Dunn.* Though the David Dunn plot change may be discussed more in-depth in a later article, it is the Staple alteration that is of immediate interest, for it appears that the initial idea was that the character would literally represent the US government, providing an explicitly political context to the picture.*

*Anyone that wants to learn more about what ostensibly was the initial plan for David in the course of Glass should read the reddit post in full. I will note that, in contrast to the “Staple as government agent” reveal, I’ve found no evidence that the “David survives and goes on the run” aspect of the ending actually ever made it to the shooting stage. At the moment then, I believe the change to David’s fate occurred early into the script’s development.

The information provided by Overseer about Staple’s background being altered due to Shyamalan wanting to avoid a polemic lines up what Samuel L. Jackson has stated about the ending to Digital Spy around the time of the film’s release:

"There was a different ending when we first started this that kind of needed to be changed because of the way society is and what's going on in the world and what it would have looked like," Jackson told Digital Spy.

Though Jackson does not go into detail, he does suggest that the ending had changed after production had started and came about due to the original being too close to or in some way invoking real-life events or discourses.

Assuming that a clandestine agency was initially supposed to be responsible for the deaths of the main characters, the original ending would certainly qualify Glass as an explicitly politicized work that invoked real-life events. So, if the ending were changed to avoid real-life discourses, it follows that the “Staple is a government agent” plotline was most certainly the cause.

Finally, there’s an article that had been published on TheNerdy.com on July 27, 2018 - six months prior to the premiere of Glass. This article claimed to spoil key plot points from the movie, especially its ending. Almost all of the narrative information the article purported to leak would end up being accurate in relation to the final film. For instance, it states:

Our sources claim that at the end of the movie, the three main characters die following a major fight, though it’s unclear how. That’s a fairly typical and expected ending, but it’s what comes next that’s very intriguing. Their deaths allegedly set off a chain of events that leads other people to realize they also have powers. Suddenly, the collective world knows that people with superhuman abilities exist.

But there is one notable difference between the article’s plot summary and the events of the released film. Here is what it says about Dr. Staple:

“Dr. Staple is said to be working for the U.S. government to try and hide the fact that there are individuals with super powers. Essentially, Dunn and The Horde are caught in the middle, with Mr. Glass and Dr. Staple acting as the manipulators.”

The high degree of accuracy between the leaks and the final film evinces that everything the article reported was true at the time of its publication.

Indeed, the author notes that Glass

“...doesn’t hit theaters until early next year, so things could always change between now and then.”

At the very least, this corroborates that Dr. Staple was initially conceived as an agent of the U.S. government, but her background was rewritten at some point between filming and release. The “government agency” reveal fits perfectly with other narrative elements that remain in the final film itself. As I noted in my defense article on the movie, the “Clover Society” functions as a metaphorical standin for state power, with the picture linking it to mass surveillance, extrajudicial imprisonment of ideological dissenters, as well as torture/violation of human rights.

The revision of the ending would explain why the Clover Society has many characteristics of a US government agency: because there was literally supposed to be a US government agency in its place in an earlier iteration of the movie. The change had allowed Glass to be more open to interpretation, as well as to function more as a political metaphor rather than an explicit statement.

Of course, several questions arise.

Was the ending where Staple is revealed to be a government agent actually filmed? Or was it scrapped before the shooting of the final scenes commenced during production and the new “Clover Society“ material was filmed in its place? In other words, is the ending that appears in the theatrical version the result of a post-production reshoot?

At the moment, I would say it is probable that it is a reshoot, but there is not enough proof yet to be absolutely certain.

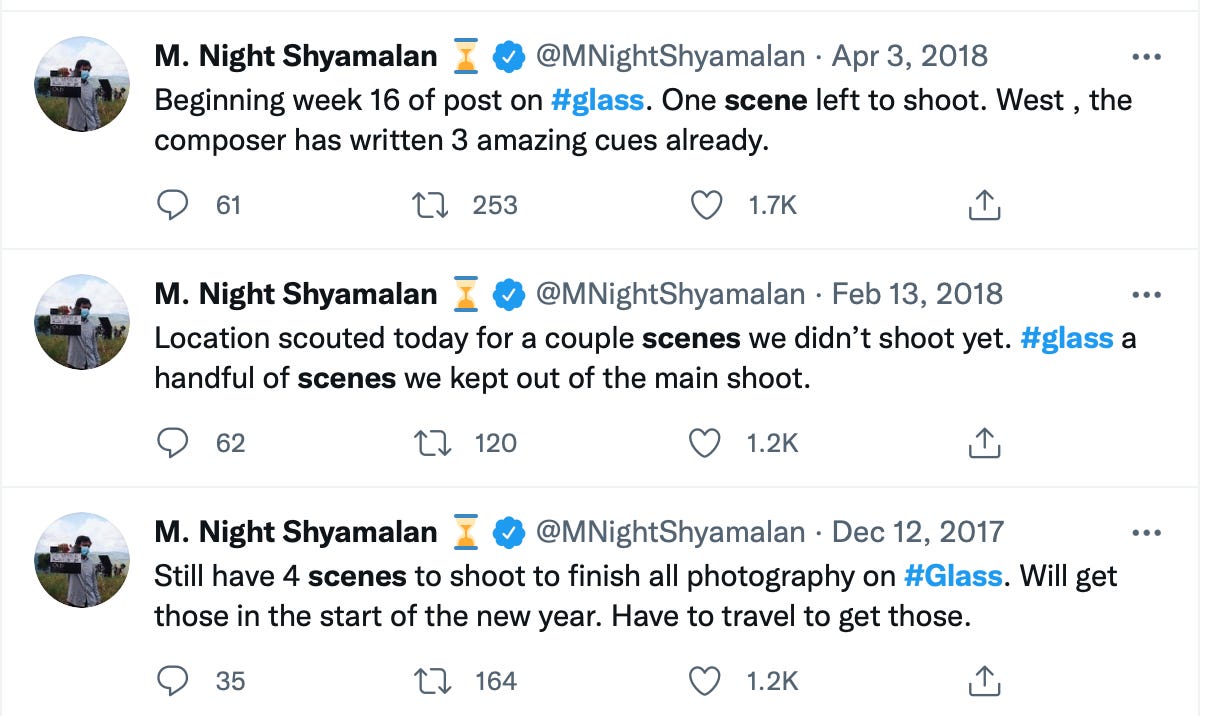

The initial Glass shoot reportedly began on Oct. 2, 2017 and wrapped on December 4. However, Shyamalan revealed via his Twitter a little later that some additional filming did occur during post-production (as late as April 2018) indicating that some time in the post schedule was allotted to reshoots and/or pickups. A new ending alongside some other scenes could’ve very well been produced during this period.

And the July 2018 report by TheNerdy.com did get almost everything that occurs in the final film correct, except for the nature of Staple, which could signify that she had remained a government agent until late into post-production.

In any case, however, the fact that Staple’s background was given a rather late-stage overhaul illustrates just how malleable and fluid the narrative of the third entry in the Eastrail trilogy really was. In turn, it gives credence to the idea that the version of the ending described in Overseer32’s reddit post, where David Dunn had survived the fight outside the hospital, overcame his fear of water and went on the run from Staple’s agency with Joseph, indeed existed in an early treatment for the film.

Going further, one can speculate that some early drafts of the Glass screenplay include this ending as well, meaning the Eastrail trilogy could’ve ended with a cliffhanger that left the door open for more of Bruce Willis’ David Dunn in the future.

All in all, the changes to the endings of Unbreakable and Glass are indicative of how the Eastrail 77 trilogy that we have now was the result of a gradual and organic evolution, rather than known or planned for years in advance. This tends to be true of all long-running stories: few longform works, whose individual chapters are produced and released years apart from one another, can be fully planned out.

Far more could be written about just how and why the overarching story of Shyamalan’s trilogy had evolved over time.

This is something I hope to delve into in the future.

But what do you think?Did you like this article? Do you think any of the alternate endings discussed here would’ve been better than what we received in the theatrical release? Did Shyamalan make the right call in changing how the films ended? Then, please,

Suggested ReadingsInterested in Shyamalan and/or The Eastrail 77 Trilogy? Then please read about how this article was plagiarized by a major film blog about six weeks after first being published:

Also, please consider:

For the theatrical release in France, there were no inserts at the end. David just left. No mentions about the police or the mental institution. These inserts surprised me when i bought the DVD few months later..