A History of Warner's Failed DCEU Superhero Crossovers

Warner Has Repeatedly Failed To Launch Solo Spinoffs

Black Adam, starring Dwayne Johnson as the titular antihero, has finally arrived in theaters. Hopes are high that this film will be a hit and help propel the DC Extended Universe of movies (DCEU) into a new phase, changing the ‘hierarchy of power’ and all that. What interests me about this movie, however, is what it will mean for Warner’s approach to making future DCEU crossover movies.

Because, despite what much of the press articles and BTS materials may claim, Black Adam is not really a ‘solo’ or ‘standalone’ movie. It actually fits into the storytelling paradigm Warner established almost a decade ago for its shared superhero universe, which is essentially that every other new DCEU film needs to be a big ‘Crossover’ or ‘Team-Up’ picture that has had little to no actual setup in prior movies.

Here then, I want to talk about this “Crossover-first” approach, trace its evolution over the years, and speculate on how the success or failure of Adam could impact it.

Table of Contents1. Beginnings

2. The Logic Behind the DC Crossover Movie Formula

6. Black Adam

Beginnings

The origins of Warner’s strategy for building out the DCEU date back to around 2012, the year that its rival Disney released The Avengers, a big crossover movie that brought together multiple Marvel characters and plot points established previously in the largely standalone (yet interconnected) solo superhero films, including Iron Man (2008), The Incredible Hulk (2008), Thor (2010, and Captain America (2011).

The initial MCU installments had a mixed reception overall, but the massive critical and commercial success of Avengers proved the validity of the MCU’s narratively-experimental-for-cinema approach to storytelling. Suddenly, every major studio in Hollywood wanted to have a ‘shared cinematic universe’ where characters from different franchises could come together and a greater degree of serialization and interconnectivity between films and their sequels.

Now, I don’t know whether Warner suddenly decided to create new DCEU plans in reaction to this or just to accelerate plans that already existed.

But whatever the case was, information on the studio’s approach to crossovers between its numerous superheroes (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, The Flash, etc.) became public as early as July 2012 in an LA Times article about the potential involvement of Christopher Nolan in a Justice League movie. Discussing some of the differences between Marvel and Warners’ approaches to filmmaking, it stated:

And while Warner would put most of its DC heroes on the big screen for the first time in “Justice League” and then potentially spin them out into their own movies, Marvel introduced four of its key characters in their own movies before teaming them up in “Avengers.”

A follow-up report that October claimed that the plan was now to shoot Justice League in 2013 for a 2015 release, while reiterating that this was to be a big team-up film meant to introduce DC’s prominent superheroes to the masses and function as a launchpad for individual future solo spinoff movies:

“The studio’s plan is to spin out other superheroes into their own movies following “Justice League.” That’s contrary to Marvel’s successful strategy of teaming up Iron Man, Thor, Hulk and Captain America in “Avengers” (which became a global blockbuster) after each character had his own film.”

While Justice League would not start shooting in 2013, an interview with David Goyer for the Empire Online Spoiler Special podcast that June gave credence to the idea that the “crossover-first, spinoff after” model reported by LA Times previously was still going to be what Warner adhered to going forward, positioning the just-released Man of Steel (2013) as the first installment of the much larger DCEU. He stated:

“This is just, sort of, y’know, ground zero for (no pun intended) a greater DC universe. This is a shared universe… if the film is well received, that this would be the starting point for introducing other characters and ultimately, obviously Warner Brothers hopes there will be a ‘Justice League‘ film and perhaps you might start seeing other characters appearing in each other’s films. I think in some ways they’re interested in going perhaps the opposite direction that Marvel has done which may be to do a group film and then spin off.”

Source: “David S. Goyer And Zack Snyder On Man Of Steel’s Secrets”

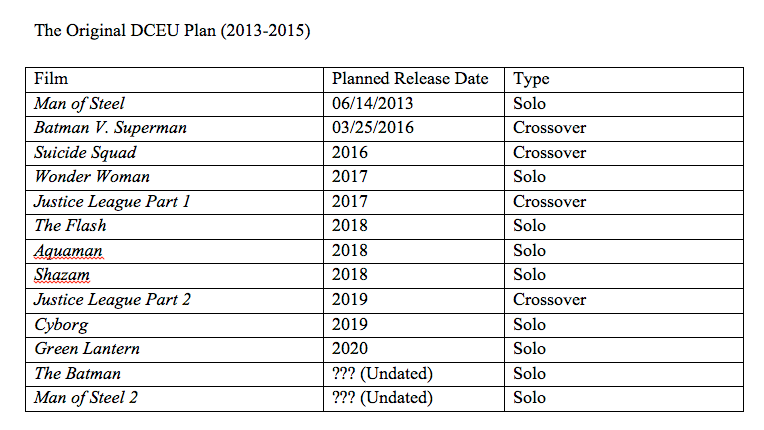

But it wasn’t really until October 15 2014 that Warner would reveal its ambitious plan for the DCEU, in the process corroborating its crossover-first approach.

Three out of the first four movies planned after MOS were going to be big crossovers that had no real prior setup. Batman v. Superman was to establish both Batman and Wonder Woman, superseding a solo introductory picture for each hero and bringing them quickly together onscreen with Superman. Suicide Squad was similarly meant to establish a bunch of famous DC villains that have not actually served as antagonists in a prior DCEU picture, including the Joker and Harley Quinn.

Finally, Justice League would prepare The Flash, Aquaman, Cyborg, and possibly even Green Lantern for their own upcoming solo adventures.

Thanks for reading Textual Variations! If you want more in-depth TV reviews or just interesting film criticism, then sign up below!

The Logic Behind The DC Crossover Movie formula

Why did Warner choose to go this route, as opposed to following Marvel’s example? I believe the main reason is time.

The MCU essentially followed the traditional approach to both building a Crossover story and constructing a larger Serialized Narrative, engaging in “procedural world-building,” to borrow a term from critic Emily St. James. Consequently, The Avengers had considerable shorthand when it came to its own specific narrative, which brought together characters and pieces of a larger story established in previous films.

Moreover, each of the MCU’s first five installments served as a potential entry point for new viewers, meaning it could be enjoyed in and of itself and did not require viewing another title either before or after to receive a complete cinematic experience. This meant that Avengers, like many crossover stories in television or comics, could pool together built-in audiences that connected with the individual solo titles.

Such an approach requires considerable time and patience, both on the part of the producers and the consumers. Marvel had the luxury of time and it did not have the pressure to get to The Avengers ASAP, as the ambitious macro-narrative storytelling it was attempting here was virtually unprecedented in Hollywood blockbuster cinema.*

*This is a point of potential debate, of course, if one considers the interconnectivity between classical Hollywood horror movies or maybe the serialized film trilogies of the 80s.

Thus, by virtue of arriving late to the shared universe party, Warner/DC had no choice but to react to Marvel, to catch up to Marvel, to move faster than Marvel. Yet it also had to define itself as distinct from Marvel.

The Crossover-first approach potentially would’ve solved all these issues.

Marvel needed at least 5 movies to launch 5 interconnected superhero franchises before further expanding the Universe. Warner/DC likely figured they could launch at least 6 interconnected franchises in three movies, saving a lot of money, a lot of narrative real estate, but most importantly, a lot of time in the process.

By the end of 2017, Warner would have introduced 5-7 new franchise leads, placing it on more even footing with its rival without directly imitating it.

Risks and Failures

I don’t think DC’s approach was necessarily bad or misguided.

Perhaps it was even necessary under the circumstances. After all, teaming up heroes from the outset before exploring them individually had been done before.* And critics seemed tired of introductory ‘origin stories’ anyway, so perhaps Warner believed it would be fine to mostly skip past all that and fill in the gaps later. But the crossover-first strategy had considerably higher risks than the traditional one.

*For example, look at the animated series Justice League, which opened by introducing 4 new heroes before doing more character-focused, smaller-scale episodes later. And consider how often animated takes on the Justice League immediately jump into their stories without showing how the Justice League is actually formed.

For one thing, it negated one of the central appeals of crossovers and serialized storytelling, which is the ability of individual chapters or series work together toward a larger, more ambitious, overall story than could be executed in a single narrative unit and that rewarded long-term audience investment.

Consequently, rather than function as a ‘payoff’ to preceding ‘setup’ chapters, each DCEU crossover movie essentially had to do the work of multiple films crammed into one. It had to be more complex, more expensive than a solo picture, with a larger scale and a longer running time to successfully accommodate the introduction of each new individual hero. And that also meant tremendous pressure to succeed, to instantly become a huge hit that resonated with viewers and made them excited to see more of everything, for the failure of the crossover could doom the planned spinoffs.

As Marvel typically focused on establishing one hero at a time, it did not initially have quite as much riding on the success or failure of each individual solo title (except perhaps Iron Man), and so could afford a few stumbles along the way. Even if not that many people liked Iron Man 2, Thor, or The Incredible Hulk, there was still a good chance they would return to see all these characters in The Avengers.

By contrast, Warner/DC could not afford to stumble with just the second installment of its Shared Universe. And unfortunately for everyone involved, stumble it did. Hard.

Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016, dir. Zack Snyder) was mostly a failure.

Sure, there are many who would likely make a case for it being an artistic or narrative success. But it was largely derided by critics, rejected by a whole lot of comic book fans, and its box office gross, though not immodest, was considerably below studio expectations.* More than that, BvS unintentionally began an unofficial trend for Warner: whereas standalone/solo DCEU movies would be successful, the crossovers would fail in one way or another.

*A blockbuster that costs around $400 million when production and marketing costs are factored in is expected to a billion dollars at the box office to be considered truly profitable.

Despite having a relatively good box office, Suicide Squad (2016, dir. David Ayer) was savaged by critics, while Justice League (2017, dir. Joss Whedon) had both a smaller monetary take and an even worse critical reception than BvS. By contrast, Wonder Woman (2017, dir. Patty Jenkins) and especially Aquaman (2018, dir. James Wan) ended up being legitimate success stories, with the latter breaking the $1-billion mark globally to become the most commercially profitable DCEU picture to date.*

*Though not all critics may not have been kind to Aquaman, audiences really seem to dig it. I personally find it to be the one true masterpiece of the DCEU, but that’s another story.

These films, however, worked largely in spite of what came before in BvS and Justice League, rather than because of it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the initial post-2018 plans for the DCEU went out the window, with Warner seeking to make more or what worked and less of what didn’t.

Evolution of the DCEU Crossover: The Faux-Lo Strategy

What is fascinating in hindsight though is how none of this signifcantly impacted Warner’s general paradigm. Even as the studio reportedly decided to pivot away from the “Shared Universe” concept in 2017 towards making more standalone movies with their own continuity (eg. The Batman, Joker) and produce more solo-hero franchise sequels, it nonetheless continued predominantly making big crossover/team-up-first pictures meant to establish potential solo spinoff franchises.

The difference here though is in the details.

Whereas its first three crossover movies were unequivocally designed as team-up pictures, most of the ones coming out post-2019 (The Suicide Squad being a notable exception) are simultaneously designed to work (and thus be marketed) as solo movies.

Consider, for example, the case of The Flash, which was intended to be released way back in 2018 before being repeatedly delayed, reconceived, and rewritten. Under the initial plan, it would most likely have been a true solo spinoff film in the vein of Aquaman or Wonder Woman. But as has become increasingly clear over the last year or two, the picture now scheduled to come out in 2023 is not really going to present a personal Flash story sequestered from the narratives of other characters, but rather another large crossover ‘event,’ with The Flash (Ezra Miller) sharing the spotlight with both Batman (Michael Keaton) and Supergirl (Sasha Calle)

Presumably, The Flash will remain the ostensible ‘lead character’ of the picture, with the other big name heroes being folded into his story as supporting or subordinate players rather than full-on plot drivers. Yet, even if this is the case, the movie would still be constructed in a manner distinct from a truly standalone superhero story devoted to the Flash’s narrative.

In effect, The Flash has over 4 or so years of development hell transformed from a true solo movie into a crossover movie disguised as a solo movie. Thus, I would propose then the correct term to define this film and others like it would be ‘faux-lo.’

Birds of Prey/Harley Quinn

Chronologically, of course, the first faux-lo movie in the DCEU thus far has been Birds of Prey and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn (2020, dir. Cathy Yan). Though ostensibly about breakout DC Comics villain Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) trying to emancipate herself from the Joker, the R-rated black comedy also introduces multiple other potential spinoff lead characters, including Black Canary (Jurnee Smollett) and The Huntress (Mary Elizabeth Winstead).

Despite its mostly positive reception, Birds of Prey did not quite make a splash at the box office in its first weekend, which led to the movie undergoing an unofficial retitling to Harley Quinn: Birds of Prey. Whereas the initial title emphasized the movie’s status as a crossover with Harley as a guest to the ‘Birds’ teamup and/or a member of a larger ensemble, the second re-positioned her as the main character and advertised the picture as more of a solo adventure.

How and why exactly this occurred is still unclear.

According to The Wrap, Warner Bros. did not actually change the name of the film. Rather, this was done by national theater chains for search engine optimization (SEO) purposes - meaning it would be easier to find and google. (This sort of retitling is something commonly done for online article distribution. In effect, you create a second title for Google that does not replace the actual title of your work.)

By contrast, The Verge attributes the SEO alternate titling change more directly to Warner itself, referring to the how “the decision to forgo using her name in the first place baffled industry members.”

It didn’t work. Rather than replicate the commercial success of DC’s solo superhero films and sell audiences on its ‘guest’ heroes, Harley Quinn/Birds of Prey considerably underperformed at the box office and reportedly did not recoup its budget.

Whether or not the film constitutes a flop remains an area of debate. But its situation, in any case, illustrated that the faux-lo movie was not a surefire guarantee of success, and that it came with an inherent difficulty when it comes to the marketing.

Do you entice viewers with the promise of multiple heroes coming together in an ensemble? Or do you rely on the appeal of a key ‘name’ character to sell the movie?

All this, coupled with the full-on box office bombing of The Suicide Squad, does not bode well at all for the theatrical release of the latest DCEU crossover.

By this, of course, I refer to Black Adam.

Black Adam

Source: “Black Adam - Official Trailer 2“ by Warner Bros. Pictures - Sept. 8, 2022.

What notably distinguishes Black Adam from Birds of Prey is that its lead has not really appeared in the DCEU before (unless one counts a holographic image in Shazam.) Harley Quinn had gotten an abridged origin story in Suicide Squad before returning in Birds, but Adam is all-new, which one could argue qualifies this as a solo picture.

But make no mistake: Black Adam is very much a crossover-first film, pitting its lead against the Justice Society of America (JSA), which consists of four previously unestablished-in-the-DCEU superheroes: Dr. Fate (Pierce Brosnan), Cyclone (Quintessa Swindell), Atom Smasher (Noah Centineo), and Hawkman (Aldis Hodge).*

*That Adam comes to function as part of an ensemble of name superheroes rather than carry the picture mostly by himself with the aid of a supporting cast seems rather ironic when you consider the fact that Dwayne Johnson was originally set to portray the titular character as a villainous supporting character in Shazam! (2019), only to petition for him to be removed, so as to be able to develop a standalone origin movie around him. One also has to wonder if Warner left the JSA out of the title to avoid repeating the marketing fiasco of Birds, as Black Adam and the Justice Society of America would’ve been a more apt name for the picture.

These characters are prominently featured in the trailers, and interviews with the cast and crew, especially Dwayne Johnson himself, make clear that the producers are hoping to build additional movies around them in the future. For instance, here’s what Johnson claims in the Total Film Magazine September 2022 Cover Story (p. 42):

“Black Adam is the anchor that will drive us with jet fuel out of the gates… But the goal is to really expand the universe, and introduce new characters, and spin off, and be really strategic about the plan. We have a few ideas of what characters people are really going to respond to in Black Adam, and so we’re already thinking ahead…”

[The cast members playing the JSA heroes, alongside producer Hiram Garcia all corroborate Johnson’s claims on pages 42-43, and apparently some ‘tentative discussions’ have already happened in regard to a potential Dr. Fate film.]

Here’s what he states in a recent interview with Entertainment Tonight (Oct 12, 2022):

“I can tell you that the whole goal and initiative of Black Adam was to build out the DC universe by introducing not only Black Adam, but the entire JSA,” said Johnson, teasing “five new superhero characters in one movie.”

Once again then, there is a LOT riding on one big crossover movie.

Should Black Adam live up to expectations, the DCEU’s crossover-first approach will have been finally validated, likely inspiring Warner-Discovery to not only spin off the JSA members into their own films but to also continue making more faux-lo pictures.

But should it fail, which I believe is likely, given what happened with all of its predecessors, then all the potential spinoffs might be cancelled, the new 10-year plan for the DCEU (assuming it really exists) could get scuttled, and we may very well never see another crossover-first or faux-lo DCEU movie after The Flash.

That is not to say Warner will give up on making DCEU crossovers.

Rather, I do believe the new management will finally stop trying to use crossovers to agressively establish new characters and go the more traditional route, using them to bring together pre-established characters. We might thus see an influx of smaller-scale, true solo pictures in the DCEU that tell more personal, isolated stories revolving around one DC superhero at a time.

Again, I don’t think the crossover-first approach is fundamentally flawed, and it would be highly reductive to attribute all the failures of the DCEU to it, especially given Warners’ tendency to mandate short running times for its team-up films. Nonetheless, while the risks of the approach have been great, the rewards have not.

That Warner has continued working with crossover-first storytelling for as long as it has, despite all its previous failures, and the regime changes that occurred in the company in the last decade, indicates that catching up to Marvel - by establishing as many heroes as possible as quickly as possible - is still a priority at the studio.

Perhaps it could benefit from slowing down, focusing, and successfully doing one thing at a time, rather than trying to do a large number of things at once and failing.

If you like this article, then please, by all means, share it!

If you’re interested in reading more about the evolution of the DCEU, please read my extensive article on the history of the Snyder Cuts.